The RightsDD guide to modern slavery risk in pharmaceutical supply chains

A RightsDD industry deep dive guide incorporating an interview with Novartis' human rights team

Disclaimer: nothing in this guide is to be construed as legal advice. This guide is for informational purposes only.

1. Overview

There are 17 million victims of modern slavery in business supply chains today1. Unfortunately, the pharmaceutical supply chain is not free of abuse and multiple incidents of slavery have come to light in recent years. Identifying and addressing modern slavery risk in today’s complex pharmaceutical supply chains is challenging; doing so is critical, however. Not only is tackling slavery the right thing to do ethically, but it also makes good business sense. Here’s why:

- Many companies are legally obliged to report on modern slavery in their supply chains. There are penalties for non-compliance with legislation.

- The import of goods made by, or containing materials made by, forced labour is prohibited in many countries, including Canada and the USA.

- Association with modern slavery can damage relationships with shareholders, investors, customers and employees.

- Proactive due diligence lowers the risk of supply chain disruption.

2. The Regulatory Landscape

The UK Modern Slavery Act 2015

The UK Modern Slavery Act came into force in October 2015. It specifies that any corporate body that provides goods or services to the UK market, and has a turnover of £36 million or above, is required to publish an annual modern slavery statement. The statement must confirm the steps taken to tackle slavery in the corporate bodies’ operations and supply chains2.

The Australia Modern Slavery Act 2018

The Australia Modern Slavery Act came into force in December 2018. The Act requires companies based, or operating, in Australia with an annual revenue of over AUD $100 million to report on modern slavery risks in their operations and supply chains. Subject companies must meet this obligation by filing a modern slavery statement annually on a government registry. Companies must take action to address any risks identified3.

Norwegian Transparency Act 2021

The Norwegian Transparency Act came into effect on 1st July 2022. The Act targets companies registered in Norway and abroad, that offer goods or services to the Norwegian market. Companies must also meet at least two of the following criteria to qualify:

- Sales revenue higher than NOK 70 million (~$8 million)

- A balance sheet greater than NOK 35 million (~$4 million)

- An average number of employees (in a given financial year) that is equivalent to, or greater than, 50 full-time staff.

The new law requires companies to perform human and labour rights due diligence, of their own operations and relevant business partners (including suppliers). This due diligence must be carried out regularly and be proportionate to the size of the business. Companies can be fined for non-compliance.

US Tariff Act 1930, Section 307 Prohibition on Import of Goods Made by Forced Labour

The import of goods made, farmed or mined by forced labor into the US is prohibited under Section 307 of the Tariff Act. The import of goods containing materials made, farmed or mined by forced labour is also prohibited. Suspect imports can be impounded and destroyed. Importers can be fined for non-compliance.

The US Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act

The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act came into effect on 21st June 2022. After that date, US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) will presume that all goods mined, produced, or manufactured in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) have been made using forced labour. Companies will have to demonstrate that goods were not made by forced labour to clear customs.

The CBP will prevent the import of all goods that can be linked to the XUAR, regardless of where the finished product is made. This means goods that contain parts or materials sourced from Xinjiang will be impounded by CBP and importers maybe fined4.

3. Introduction to Modern Slavery

Modern slavery is an umbrella term for a group of human rights abuses including forced labour, debt bondage, and the worst forms of child labour. To address modern slavery risk, the UN Guiding Principles on Business & Human Rights (UNGPs) confirm that companies should engage in human rights due diligence5.

3.1 Definitions

- Debt bondage – Debt bondage exists when people are forced to work for their employer in order to pay off their travel/ recruitment/ accommodation debts.

- Forced labour – The International Labour Organisation (ILO) defines forced labour as ‘all work or service which is exacted from any person under the threat of a penalty and for which the person has not offered himself or herself voluntarily’.

- Human rights due diligence – A management process used to prevent, mitigate, and account for how [an organisation] addresses its adverse human rights impacts.

- Worst forms of child labour – Involves children being enslaved, separated from their families, exposed to serious hazards and illnesses and/or left to fend for themselves – often at a very early age.

3.2 Modern Slavery Due Diligence

Modern slavery due diligence is based on the process of human rights due diligence defined in the UNGPs, but focuses on modern slavery risk to workers. Modern slavery due diligence is a four-stage process:

- Engage with suppliers to gather data for assessment. This data should preferably be complemented by third party sources.

- Assess the goods and services your company buys and the companies that supply them for actual cases of slavery and procedures and practices that create a risk of exploitation. Use the data provided by your suppliers, third parties and independent analysis.

- Act to address actual instances of modern slavery that have been identified and mitigate risks.

- Monitor supply chains for new risks, as suppliers that are low risk at the time of assessment may become higher risk at a later stage.

Throughout the due diligence process, you should communicate with key stakeholders. It’s important to note that you are not expected

6 to know everything that’s going on in your supply chain. In most cases, that’s impossible. Rather, you should employ a risk-to-people based approach to identify the highest risks areas of your supply chain. For further information see our

guide to modern slavery due diligence.

3.3 On the Ground AssessmentsIdeally, your company’s employees will visit facilities in your supply chain on a regular basis. If this is the case, they should be trained to monitor for the warning signs of modern slavery. For more information see below. Companies may choose to train personnel to conduct audits of suppliers. These ‘second party’ audits are typically conducted by personnel who don’t have a relationship with the supplier under audit. As an alternative or complement, audits can be commissioned from third parties. It is critical to ensure that auditors have a strong understanding of human rights and are truly independent of the companies they will be auditing. Audits can provide valuable insights into modern slavery risk, but should not be a company’s sole form of due diligence. They can be gamed, for example by falsifying records of working hours, and provide only a snapshot insight of employment practices in a given facility at a given time.

3.4 TrainingTrain your people to help them identify and spot the warning signs of modern slavery. All training courses should be appropriate to the employee's role. For most employees, a short course -such as our

free modern slavery training course- should be sufficient. We normally recommend that personnel who buy on behalf of your company are given enhanced training. Other specialist personnel (e.g. legal) may also benefit from more extensive training. Courses that are tailored to your company tend to have the most impact and you may consider developing your own course in-house. Alternatively we can develop a tailored

modern slavery course for you.

3.5 The ILO’s Indicators of Forced Labour

The ILO have compiled a list of eleven indicators that “represent the most common… clues” of forced labour. The indicators can help identify victims of abuse at factories in your supply chain. The ILO note that the “presence of a single indicator… situation may… imply the existence of forced labour. However, in other cases you may need to look for several indicators.”

- Abuse of vulnerability

- Deception

- Restriction of movement

- Isolation

- Physical and sexual violence

- Intimidation and threats

- Retention of identity document

- Withholding of wages

- Debt bondage

- Abusive working and living conditions

- Excessive overtime

See the

ILO for further information and case studies.

4. The Pharmaceutical Supply Chain

4.1 Overview

The Pharmaceutical industry and its supply chains are immense. The ex-factory value of pharmaceuticals manufactured globally in 2021 was $1 trillion7. At least 5.5 million people worldwide were employed in the pharmaceutical industry and 45.1 million people in its supply chain in 20218.

4.2 Modern Slavery Risk in the Pharmaceutical Supply Chain

The pharmaceutical supply chain is one of the most complex of any industry. It extends into many different sectors, including waste management, clinical trials, transportation and distribution, site operations, security services, travel, and recruitment agencies9.

The pharmaceutical supply chain is comprised of four key tiers:

Tier 1: Raw Materials are unprocessed, primary materials. They may be used directly, or subject to one or more stages of processing before being incorporated, in a drug. This tier extends into high-risk countries and sectors, including manufacturing, construction, mining, agriculture, and personal services10.

The Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Initiative (PSCI) reports that Tier 1 is one of the opaquest areas of the supply chain, and that it also holds the highest risk of modern slavery11. Pharma raw materials are diverse in type and are sourced from around the world.

Companies can use a risk assessment matrix to identify higher risk raw materials. Risk factors to consider include: government, NGO and media reports linking goods to forced labour; the prevalence of slavery in the manufacturing country; and data collected from on-site assessments.

Tier 2: Primary Manufacturing is when Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) are made. Pharmaceutical companies purchase the raw materials needed to create their product, and transport them to a factory (typically in a more developed country). There is a need to avoid cross-contamination of products and equipment, which requires cleaning, changeover services, and multiple production locations. Pharmaceutical companies often don’t manufacture APIs but rather buy them as finished goods or outsource their manufacture.

60% of APIs are manufactured in China and India. It is critical that any due diligence exercise should map and assess the supply chain’s exposure to these two countries as each carries a high modern slavery risk; there are an estimated 3.8m enslaved people in China and 8m in India12.

Tier 3: Secondary Manufacturing is when APIs are turned into administrable products such as tablets and capsules. Manufacturing locations are often separate from the primary manufacturing locations and exist in far greater quantity to serve local and regional markets. Companies that sub-contract this stage of the manufacturing process should have a high degree of leverage to both assess conditions in factories and drive improvements where required. Companies that buy off-the-shelf should conduct assessments of prospective suppliers to determine the site of manufacturing and associated modern slavery risk profile.

Tier 4: Marketing and Distribution is involves the sale, marketing and distribution of a drug. Sales and marketing activities generally carry a low risk of modern slavery.

There have been multiple documented cases of labour abuse in the distribution sector, primarily involving the exploitation of freelance independent subcontractors. Pharmaceutical companies should engage with logistics partners to determine whether their workers are employees or sub-contractors. Those that rely heavily on sub-contractors should be treated as higher risk, and an assessment of their sub-contracting policies and practices should be undertaken.

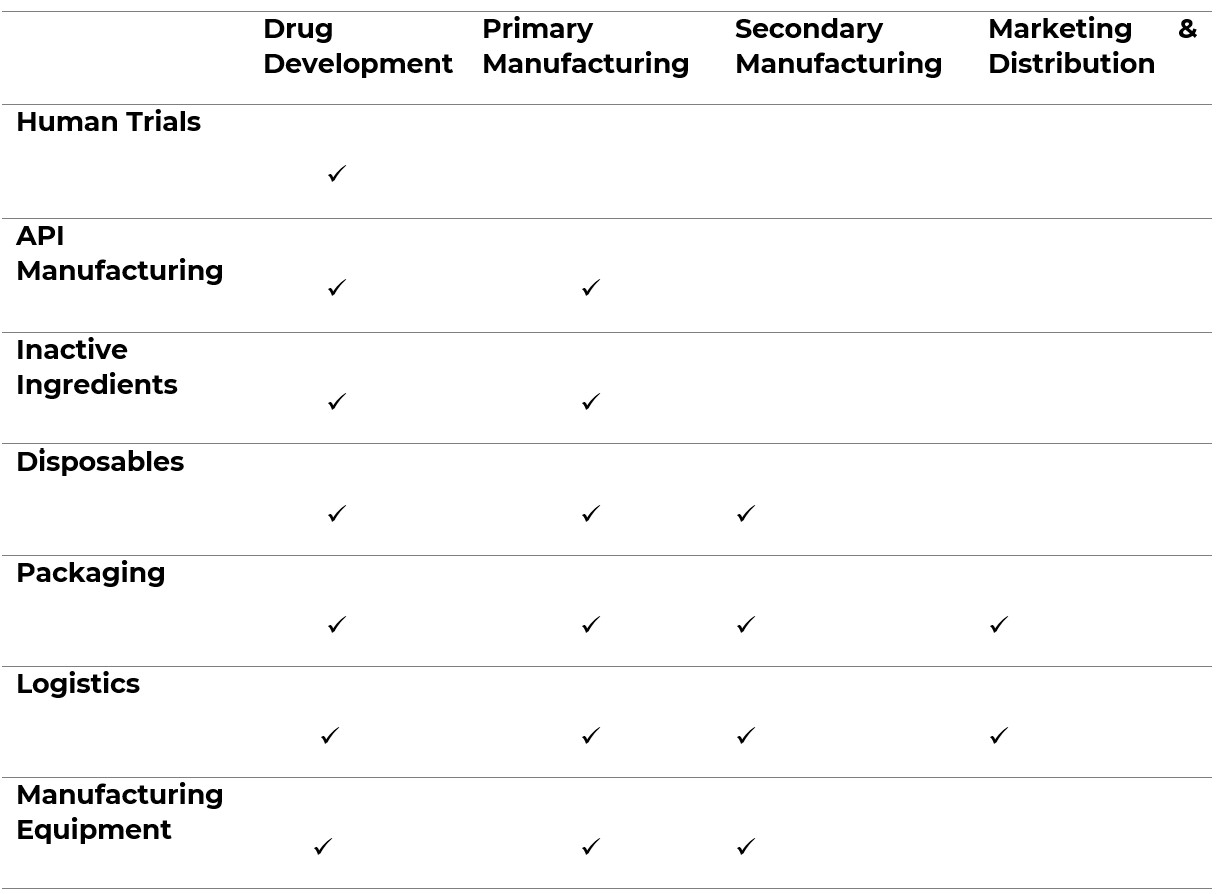

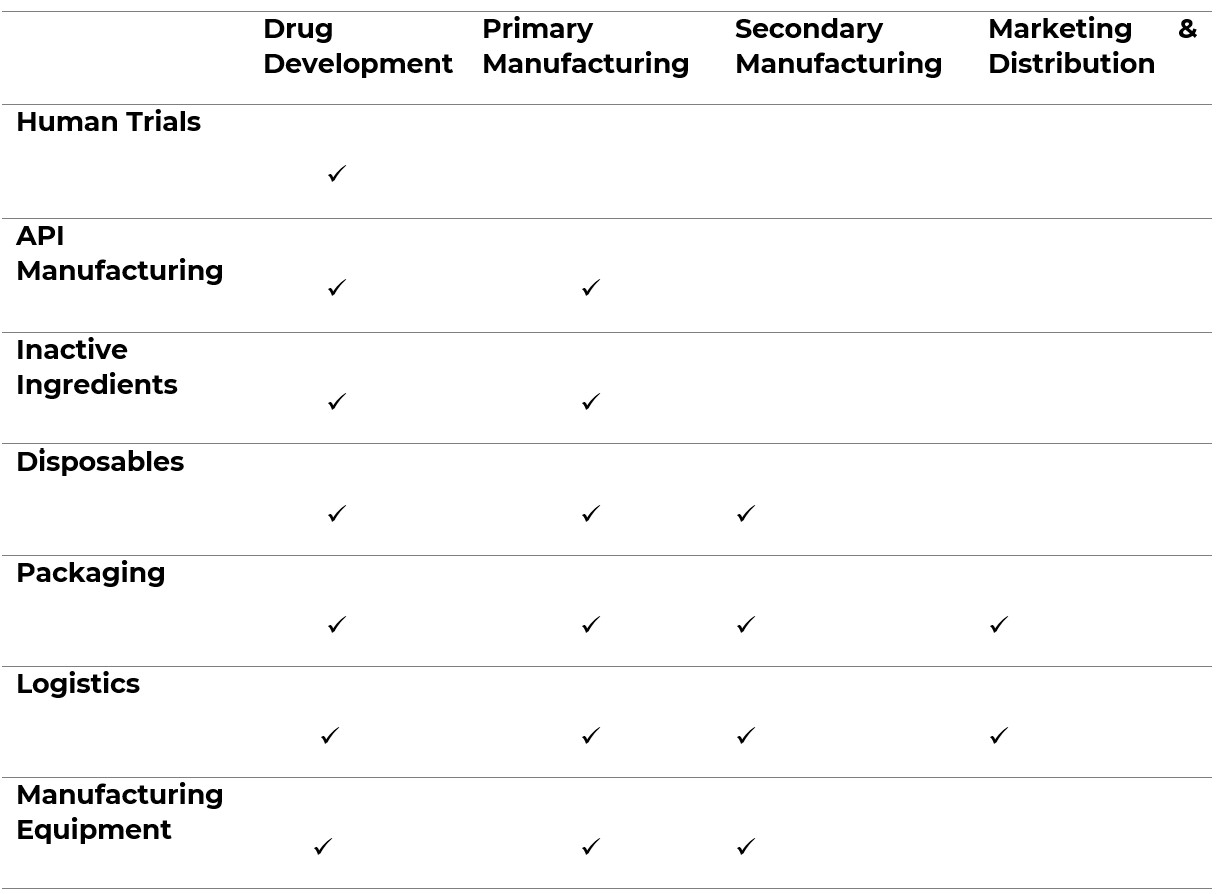

Figure 1. illustrates which sectors/materials appear in each stage of the pharmaceutical supply chain:

4.3 Drug Development

Drug Development runs adjacent to the pharmaceutical supply chain and presents its own human rights risks. The most prominent risk arises from clinical trials on human subjects. Human trials should be run in accordance with the principles defined in the Declaration of Helsinki13. The management of human trials in a manner that respects the human rights of subjects is beyond the scope.

Specifically in relation to modern slavery, it is imperative that clinical trial organisers ensures that those entering the trial give their free, prior and informed consent. Drug development companies that outsource the clinical trials must assess the organiser’s policies and practices to meet these objectives.

4.4 Ancillary products and services

Pharmaceuticals companies will typically procure products and services that are not drugs or their constituent parts, but that are necessary to function. Many ancillary products and services have a medium or high modern slavery risk14.

Examples of ancillary products and services include materials to package products and logistics partners to ship them. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) has always been widely used in drug development and production. In the Covid-19 era, PPE is now also widely used across operations, from warehouses to offices. Cleaning, catering and security are widely outsourced throughout the pharmaceutical industry; all of which often rely on lower paid workers, often from vulnerable migrant communities.

Personal Protective Equipment

Malaysia produces 62% of the world’s rubber gloves. The industry is heavily reliant on smallholder farmers to grow rubber (600,000 are involved in the Malaysian industry alone) and migrant workers to make the gloves. Whilst the farming sector is not free from abuse, it is in the manufacturing sector where significant forced labour issues have been identified. The US Government currently prohibits the import of gloves made by four Malaysian manufacturers on forced labour grounds, including industry majors Brightway and the YTY Group. A ban on imports from Top Glove, the world’s largest producer, was lifted in September 202115.

The abusive practices sighted by US officials as grounds for the embargo are illustrative of the risks facing migrant workers. Limited understanding of host country languages, laws and customs can make them vulnerable to exploitation. The US Government cited evidence of debt bondage, excessive overtime, and retention of identify documents.

Other types of PPE have been linked to modern slavery, including face masks from China, Hong Kong and Mexico.

5. High Risk Materials

RightsDD has compiled a list of materials with higher modern slavery risk that are used in the pharmaceuticals industry. To receive the full report, including the list, complete the form at the bottom of this page.

6. Case study: Novartis

Edited transcript of interview conducted with Novartis in March 2022.

Personal backgrounds

Peter Nestor is the Global Head of Human Rights at Novartis. Prior to joining Novartis, he led BSR’s Human Rights Advisory practice.

Aditi Wanchoo is a Senior Manager in the Human Rights team at Novartis. Prior to joining Novartis, she led Adidas’ Modern Slavery Outreach Program.

Could you give us some insights into how you’ve made the case for human rights due diligence internally – both at a senior and operational level?

Novartis: At a senior level, human rights due diligence is quickly becoming a legal compliance issue. We also increasingly get human rights specific inquiries from investors, external stakeholders, rating agencies, and employees. On an operational level, we have pulled away from a companywide modern slavery training programme and instead prioritized targeted and action-oriented training. We have also established a voluntary human rights ambassador network. The members partner with us on pilot projects in high-risk countries.

What is your approach to supplier engagement and how successful do you think it’s been so far?

Novartis: Our overall approach to supplier engagement is through our Third-Party Risk Management (TPRM) program. Third parties are required to complete a Third-Party Risk Questionnaire (TPRQ) and are required to implement Corrective and Preventative Action Plans (CAPAs) should serious risks be identified. In some cases, CAPAs are reinforced by on-site auditing and monitoring.

The second approach is through our global human rights team, who deal with the highest risk issues. For example, during our Human Rights Impact Assessment (HRIA) in Singapore, we identified a potential risk in our supply chain related to foreign migrant labour and recruitment fee payments. We are now running pilot projects in Singapore and Malaysia designed to develop appropriate management systems to track the payment of recruitment fees by workers and provide remediation where necessary.

Tier 2: Primary Manufacturing is when Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) are made. Pharmaceutical companies purchase the raw materials needed to create their product, and transport them to a factory (typically in a more developed country). There is a need to avoid cross-contamination of products and equipment, which requires cleaning, changeover services, and multiple production locations. Pharmaceutical companies often don’t manufacture APIs but rather buy them as finished goods or outsource their manufacture.

60% of APIs are manufactured in China and India. It is critical that any due diligence exercise should map and assess the supply chain’s exposure to these two countries as each carries a high modern slavery risk; there are an estimated 3.8m enslaved people in China and 8m in India.

Do suppliers engage when you ask them about human rights?

Novartis: Yes, but there are challenges. For example, most pharmaceutical companies procure raw materials which are usually several tiers below our direct suppliers. The problem is that most companies are buying raw materials in small quantities – which gives them limited leverage. It is important to continuously engage with supplier management teams. Usually, they are willing to change practices that they had not considered to be exploitative; like holding workers’ passports. When leverage is low, cross-sectoral collaboration can help.

Can you give an overview of your rightsholder engagement program?

Novartis: Since 2017, we have conducted eight in country Human Rights Impact Assessments, which involved engagements with over 200 rightsholders ranging from internal employees to third parties to civil society organisations.

Could you give us a quick overview of the collaborative approach you’re trying to foster at PSCI?

Novartis: Since 2018, we have played a leading role in the Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Initiative (PSCI), including chairing the Board in 2019. In 2021 we collaborated with our PSCI peers to develop a collective approach to continue addressing human rights risks in the carnauba wax supply chain in Brazil. Collectively we identified and engaged with five carnauba wax processors that control 95% of the carnauba wax coming from Brazil. The purpose of the collective engagement was to obtain information on the steps taken by each producer to investigate, mitigate, and/or remediate allegations of forced labor at the farm level, and to understand their monitoring mechanisms going forward.